I have written a hymn for use on the Fourth Sunday of Advent, Year C. That's this Sunday, December 23rd. It is sung to the tune for "Silent Night, Holy Night," (or "Stille Nacht" in the original German). It is written in memory of the Reverend Chip Gunsten, the Assistant to the Bishop of the Virginia Synod (ELCA) who died rather suddenly last week. I give my permission to anyone who wants to use it, with acknowledgement.

Wednesday, December 19, 2012

Wednesday, November 28, 2012

Life of Pi and Christ the King

About eight years ago I

attended my first-ever book club meeting, and at that meeting one of the

members gave a review of the book Life of

Pi by Yann Martel. The reviewer did an outstanding job elucidating the

themes of the novel, but in doing so divulged so much of the storyline that I decided

I needed to have ample time to forget what he’d said about the book before I ever

read it myself. Alas, that never really happened, but seeing the trailers for the

Life of Pi movie became impetus

enough for me to find a copy of the book and read it anyway. I figured I wanted

to have the book’s version of the story in my mind before I corrupted it with

Director Ang Lee’s adaptation. And so I got my hands on a copy of the book and finished

it quickly so I could see the film on its opening weekend, which happened to

coincide with the weekend of the liturgical festival of Christ the King.

Overall, I was fairly pleased

with the director’s outcome. I was worried when the opening credits claimed it

would be “based on” the novel by Yann Martel—such a wording suggested, at least

to me, that it might stray too far from the book plot and what the book’s

author was trying to say. However, the basic thrust of the book was pretty much

left intact. Admittedly, the book presents some significant filming and

storytelling challenges. There are constantly switching of points-of-view,

complex philosophical subject matter communicated through a wordy narrator, and

the almost unrealistic scenario of a teenage boy and a Bengal Tiger spending

over 200 days as castaways together on a lifeboat in the Pacific. That said,

the movie does a pretty good job, especially on the first and third points. The

flashback scenes do not get too confusing, and the visuals are stunning. It is

on that second point, however, where the movie gets a little too thin, and that’s

what I found most interesting about the book.

“Thank you. So it is with God.” That line, taken directly from the novel, comes right

at the end of the story and is basically the sole theological statement from Martel’s

novel that makes it into the film. That is a shame. I find that one brief

remark is not enough in spurring moviegoers to ponder what the novel gets its

readers to do. When Pi asks the young struggling writer (in the movie) and the Japanese

insurance investigators (in the novel) which version of the lifeboat story they

prefer, Martel is essentially asking the reader to examine and weigh the

competing stories of truth and authority in his or her own life. In other

words, if the novel asks a question, it would be “Which story will you live by?”

The character of Pi, whose life and witness intends to offer an apology of

sorts for religious truth, is pleased when they choose the more fantastic and

uplifting—yet equally improvable—version. What the novel manages to include

(and the film does not) is the back story regarding Pi’s thoughts on religion

and story in general. People who only see the film are likely to hear Pi’s

summary line and surmise that the movie is a statement on the fairy tale

falsity of all religions. Nothing could be further from the truth, according to

the book.

Life of Pi

is a thoroughly post-modern tale. That is, it begins head-on with the

realization that that in our day and age no overarching narrative or story can

be fully proved, which presents a huge problem in this post-Enlightenment era

when verifiable facts are “king.” Gone, too, are the days of absolute trust in

the historical claims of religion (if they ever really existed at all—but that

is a question for another time). No one can “prove” the existence of God, but

neither can anyone prove that a purely scientific worldview helps someone lead

a better life. Likewise, some may find God and religion a cop-out when it comes

to explaining the origin and purpose of life. Science, however, has been shown

to fall short of that agenda, too.

This is represented best by

the bumbling Japanese insurance investigators in the film and the novel. The

dry and clumsy investigators may be able to use science to verify certain immediate

factual claims about life—like, for example, whether bananas float (an

important scene left out of the film)—but they will never be able to discover

why the freighter Tsimtsum sank in

the first place. Even if they were to locate the wreckage at the bottom of the

Pacific, the shattered hull and rusty ship components would likely offer few

clues as to how it all went down. And there are other related questions that

may shed light on the matter, but all their answers just as elusive: who was in

charge of the ship when it sank, or just before? Why were the animals out of

their cages running around on the deck? These are all the chief concerns for

science and its accompanying authority of verifiable fact, but ultimately they

are unresolvable, unable to be proven. This applies to the same questions about

the beginning of the universe and the meaning of all life. Science can only

answer such questions in a proximate manner—getting us ever closer to the source,

but never really there, and never really being able to prove anything “once and

for all,” anyway.

Pi—and one would assume

Martel (but not Ang Lee?)—is more concerned then with the life that occurs after

that universe comes into existence. That is, Pi’s fascination with religion and

God end up helping him live more fully in the time after the ship sinks.

Through this experience, and his recollection of it, he is able to see that

everyone lives by a story. Everyone lives by an authority, whether they admit

to it or not. His brother Ravi is therefore just as religious as he is, even

though Ravi does not believe in God and thinks Pi’s love for it is silly . Ravi’s

religion—his story and authority--are sport and fitness. The story his mother “prefers”

is family history and heritage. His father, like the Japanese insurance

investigators, has chosen science. Only Pi has really awakened to the fact that

his religion(s) and belief in God have opened his quest for authority and truth

to the ultimate questions: Why am I here? Who is behind all of this? To whom do

I belong? How do I live a good life? And so on. When Pi says, “Thank you. So it is with God,” he is not

rejecting the usefulness of scientific discovery or the types of fulfillment found,

for example, in sports. Rather, he is revealing that the authority provided by

faith is a better way to understand and grapple with the joys and tragedies of

the real human existence, the historical truth-claims of various religions notwithstanding. Therefore, in a thoroughly post-modern sense, it is

true.

And so taking in the messages

of Life of Pi on Christ the King

weekend provided for a nice coincidental lens by which to view both. I’d be

surprised if Ang Lee did that on purpose. You see, the western Christian

commemoration of Christ the King is a liturgical festival essentially about

authority and which—or, better yet, whose—story we will all ultimately live by.

It was placed on the calendar in the early twentieth century (ironically,

coming to rest in 1965 at its current place at the end of the church year at

the same time the plot in Life of Pi

takes place) as a way to counter the rise of secularism and its ugly step-siblings

fascism and Marxism. It was a statement, in the face of science’s rapidly

rising confidence, that facts were not “king.” Christ is. The emphasis of the

festival is on Christ’s humble authority as displayed on the cross, but also on

the fact that the truth offered in Christ’s life—sacrificial love, the power of

meekness, the steadfast obedience to God’s will rather than one’s own—is the

truth that all the universe will ultimately live by, the truth to which Christians

believe all must one day testify. Just as Pontius Pilate was left wondering

what kind of king Jesus might be and what the nature of his truth was, if we

are honest with ourselves, we all struggle at some point with the ultimate

questions of life and life-defining authority…not the technicalities of how the

big ship went underwater, but how to live a beautiful life once we’re trapped

on the boat with the tiger and, at long last, safely make our way to land. Pi

has figured out that God is the only one who can truly help us do that, as irrational as that sounds to the unbeliever's ear. As he tells his inspiring story and makes his apology for religion, Pi's patience with the doubt of young writer and the insurance investigators is great. May Christ,

our long-suffering King, display similar patience with ours.

Tuesday, October 30, 2012

Sonnet: Mark 10:46-52

To call this man from Naz'reth "David's Son"

Did more than state his claim to Zion's throne.

It meant that Judah's waiting days were done,

The grace of God would now be fully known.

Yet not by crowds in trembling expectation

Nor by disciples--friends who knew him best--

And not by priests in hymns of adulation

Was Jesus with such boldness first addressed.

Instead outside the gate of Jericho

Unruly Bartimaeus blurts it out.

This blind and begging man springs up to show

What faith in Jesus' mercy is about:

To call on Christ, whose kingdom comes today,

And, sight regained, to follow on His way.

Did more than state his claim to Zion's throne.

It meant that Judah's waiting days were done,

The grace of God would now be fully known.

Yet not by crowds in trembling expectation

Nor by disciples--friends who knew him best--

And not by priests in hymns of adulation

Was Jesus with such boldness first addressed.

Instead outside the gate of Jericho

Unruly Bartimaeus blurts it out.

This blind and begging man springs up to show

What faith in Jesus' mercy is about:

To call on Christ, whose kingdom comes today,

And, sight regained, to follow on His way.

© Phillip Martin, 2012

Thursday, September 13, 2012

Sonnet: Mark 8:27-38

Among the empire's gleaming monuments

To human strength and military power--

Attempts to leave eternal testaments,

Withstanding time's attack like fortress tower--

The man's disciples reach a turning point

And questions of identity arise.

Is he Messiah, one God did anoint?

The Son of Man, but somehow in disguise?

Thus gathered there, his kingdom they are taught:

True living comes through dying, gain from loss;

Denial of self, divine things to be sought...

And his most lasting monument--a cross!

Turn us to know and follow Christ who shows

The blessed, risen life his death bestows.

To human strength and military power--

Attempts to leave eternal testaments,

Withstanding time's attack like fortress tower--

The man's disciples reach a turning point

And questions of identity arise.

Is he Messiah, one God did anoint?

The Son of Man, but somehow in disguise?

Thus gathered there, his kingdom they are taught:

True living comes through dying, gain from loss;

Denial of self, divine things to be sought...

And his most lasting monument--a cross!

Turn us to know and follow Christ who shows

The blessed, risen life his death bestows.

© Phillip Martin

|

| ruins at Caesarea Philippi

|

Wednesday, August 08, 2012

And so it begins...

|

| This is not the classroom, but it looked a bit like this |

Today we met a very important

person for the first time. In order to complete her screening for kindergarten,

Melinda and I took our 5-year-old Clare to the school where she will begin school

in about four weeks. In the process, of course, we got to introduce Clare to

the woman who will be her kindergarten teacher. This will be the person who

turns Clare on (or off, or to lukewarm) to learning in the school environment,

the person who will shape her day and mold her thinking over the next nine

months almost more than we, her parents will. She will teach her how to read

and show her how to use technology (there are four new iPads in the classroom).

Like I said, important person.

Needless to say, it is

easy to make too big a deal about these kinds of things, and there are plenty

of blogs out there written by what I would consider to be anxious, over-protective

parents who obsess over the tiniest detail of their child’s education. While I

don’t think I’d put myself in that category, I must be honest and say that ever

since I read this article two years ago I’ve been especially curious and

apprehensive about what my daughters’ kindergarten environments might be like.

We’ve heard great things about this school and the teachers from just about

everyone. When we walked into the building for the first time today, it felt

smaller and more intimate than what I remember about the three bland-looking elementary

schools I attended. We learned that Clare will be in a “pod” (that was new to

me) with three other kindergarten classes, but there will be only one teacher

in her class. We saw the playground (which seemed a little small, in my

opinion) and walked past the media center (or was it the library? Back in my day of cassette-tape read-along books, those were one-and-the-same). All in all, it seems like a great place, but I knew that the relationship

between Clare and her teacher would be the key component. Clare is not the most

outgoing kid, but she can open up around adults if they are patient and calm. All

the whiz-bang technology in the world and the fanciest, most intellect-stimulating

wall decorations will not make up for a lack of communication and trust between

Clare and her teacher. Put 40 iPads in that room and it won’t mean a thing if

the teacher doesn’t stop to listen to Clare and give her time to think.

And, I am thankful to say

that part seemed to go well. As I had predicted, Clare opened up very slowly

and acted a bit overwhelmed. The teacher, however, was patient and composed.

She tried very carefully—and finally succeeded—in making a connection with

Clare. I tried to be as silent as I could through the whole visit (which is

hard for me) so that Clare and her teacher could get as comfortable as they

could in an hour without my becoming a crutch for either of them. Meanwhile, I observed the room. Colors

everywhere. It looked like everything had a label. It has probably been about,

oh, 32 years since I was last in a kindergarten class, but have they walls always

been this busy? I noticed that there will be nineteen students in Clare’s

class. Six of their names start with “C.” Overall, thirteen of the students are

girls. There were a few pictures of presidents on the wall. Number tables.

Numbers over the letters over the whiteboard. Boxes and bins for all kinds of

assignments. Most of the books on the bookshelf were of the Dr. Seuss variety. It

was an assault on the senses, as Melinda said. The teacher is young—about my

age, maybe a little younger—but she seems to have clear opinions of what works

and doesn’t work in the elementary school environment. I guess an informed,

headstrong kindergarten teacher is a good thing. She must have mentioned the

word “literacy” about a dozen times. There will also be something called a

Promethian Board in Clare’s room, whatever that is.

Am I still nervous and

apprehensive? I don’t think so, but it does make me reflect a little more on

the decisions Melinda and I have made about our daughters’ education. Neither

of us has taken an overly-active role in teaching her reading or writing before

this point. I have no way of knowing how we compare to other parents in this regard.

I am not an educator or pedagogue, and the reason why I have taken very few

steps to teach our girls formal lessons is because I kind of think I’ll screw

it up. They also haven’t seemed ready to latch on to that stuff. But when I

watched Clare complete her screening “test,” I naturally wondered if the

teacher thought she was “advanced” or “average.” She did just fine, but

naturally there were some small questions she missed. Why haven’t we taught her

our home phone number yet? I didn’t realize they would ask that! When we

started talking about the assessments for giftedness that would come in the

future, I pondered where Clare would fall on those scales and—more importantly—how

I might react to the results. As a student, I was far too caught up in various

labels and intellectual categories. Had I left those prejudices behind? Had we done enough in this first

five-and-a-half years to get her ahead of the curve? Will this public school

environment stunt her true abilities? We have friends who home-school their

kids. Was their frustration with/disdain for/mistrust of the school system

something we should be considering ourselves? What about parochial school,

where classes would be smaller and some type of religious component might be

included? Private school? Maybe there she'd get P.E. more than once a week. Don't they realize she might be the next Misty May-Treanor? There are so many decisions, so many influences. It’s easy to see why

many parents start to obsess about all those little details.

Before the meeting even

began, we were sitting out in the foyer area waiting for her teacher to finish

an earlier meeting. Right as we made ourselves comfortable in the chairs, Clare

pulled a random book off of a bookshelf there and asked Melinda to read it to

her. It was an illustrated book that told that old fable about the poor farmer

and his daughter who take their little donkey to town to sell some things in

the market. You know how the story goes. They begin walking alongside the

donkey together, happily. Before too long, they happen upon a person who is

perplexed as to why the young girl would be walking rather than riding the

donkey. So the father puts her on the donkey, and they continue on their way.

The next person they see is aghast that the young, able girl is riding the

beast of burden while the older, tired father is walking. They switch places. By

the time they get to the market, they’ve switched places and tried so many kinds

of combinations with that poor donkey that all three of them are exhausted.

They also ended up the same way they started.

I guess I’ll view Clare’s chance

book selection as prophetic in this instance. That is, Melinda and I have decided

that this kindergarten and this teacher and this public school system are going

to be just fine for us. This is the combination that seems to work for now, and

I can’t imagine that would change. I’m sure from time to time I’ll allow myself

to be persuaded by those who might question us—directly and indirectly—about the

choices we’ll make for their futures. More likely, Melinda and I will begin to

doubt ourselves and wonder if we’re reading things the right way or challenging

them enough at home or stepping in to intervene when we really should just sit

in the corner and play with the iPads some more. To a degree, all of this—like so

much of life—is out of our hands, anyway, and we’ll just need to learn to be

happy with the donkey we’ve ended up with (and by that I don’t mean the

teacher, but the system) and ride it the way it feels best for us. We'll get to town just fine...even if we have to stop occasionally to read the busy bulletin boards.

Tuesday, August 07, 2012

Sonnet: John 6:24-35

Across the lake, by thousands soon they came,

Their sights set on this wonder bread creator.

They ate their fill, yet sought more of the same

For hunger is a constant motivator.

In fact, this sign of loaves beside the sea

Reminded them of their ancestors' craving

When manna was the answer to their plea,

A desert sign that God was leading, saving.

Yet all the gifts our Father's ever given

Are but mere foretastes of the Son, whose role--

Whose mission--is to be true bread from heaven

That satisfies the hunger of the soul.

Lord, give today this Bread of Life anew

That in our faith we learn to feast on you.

Their sights set on this wonder bread creator.

They ate their fill, yet sought more of the same

For hunger is a constant motivator.

In fact, this sign of loaves beside the sea

Reminded them of their ancestors' craving

When manna was the answer to their plea,

A desert sign that God was leading, saving.

Yet all the gifts our Father's ever given

Are but mere foretastes of the Son, whose role--

Whose mission--is to be true bread from heaven

That satisfies the hunger of the soul.

Lord, give today this Bread of Life anew

That in our faith we learn to feast on you.

© Phillip Martin

Tuesday, April 10, 2012

Sonnet: Luke 24:36-48

For the gospel lesson in two weeks...

In retrospect they might have known his face

Or recognized his gait, that tone of voice,

And at his word of peace their friend embrace,

This rendezvous a reason to rejoice.

Instead they freeze in fear and disbelief,

And he's reduced to showing hands and feet,

And what should be a scene of deep relief

Becomes a test to prove that ghosts can't eat.

And still they find his passion undeterred,

His risen presence just as Scripture planned!

Amidst their wonderment he gives his word:

They go as witnesses to ev'ry land.

Your grace compels us: spread this news about.

You conquered first the grave. Now conquer doubt.

In retrospect they might have known his face

Or recognized his gait, that tone of voice,

And at his word of peace their friend embrace,

This rendezvous a reason to rejoice.

Instead they freeze in fear and disbelief,

And he's reduced to showing hands and feet,

And what should be a scene of deep relief

Becomes a test to prove that ghosts can't eat.

And still they find his passion undeterred,

His risen presence just as Scripture planned!

Amidst their wonderment he gives his word:

They go as witnesses to ev'ry land.

Your grace compels us: spread this news about.

You conquered first the grave. Now conquer doubt.

© Phillip Martin, 2012

|

| "Christ Risen from the Tomb" Bergognone (ca. 1490) |

Tuesday, March 20, 2012

Athanasius on wrestling

Every once in a while I crack open my copy of Athanasius' On the Incarnation and re-read a few sections. Sometimes I just flip open to a random page and see what I find. It's always good. But what I like best is the fact that this little book was written about 1700 years ago and that it still has the ability, like Scripture, to clarify things that should seem so obvious by now. I dare say I find more inspiration and solace in these "golden oldies" than just about anything published nowadays.

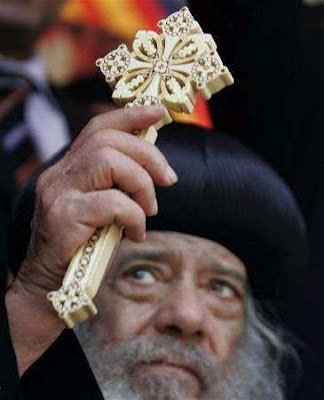

So, in memory of Shenouda III, the Pope of the Coptic Orthodox Church who died this week after serving as Patriarch for 41 years, I post this portion of Part XXIV where Athanasius discusses the signifance of the particular the manner of Jesus' death. Athanasius, too, was a Copt, and from what I can tell, had some similar personality traits and career paths with Shenouda, despite living at such different times in world history. Both endured exile at one point or another, for example. Both prevailed in expanding the reach of their communion. May the witness of all the saints--ancient, recent, and contemporary--bless us and lead the Church, the body of Christ, toward greater unity.

3. And just as a noble wrestler, great in skill and courage, does not pick out his antagonists for himself, lest he should raise a suspicion of his being afraid of some of them, but puts it in the choice of the onlookers, and especially so if they happen to be his enemies, so that against whomsoever they match him, him he may throw, and be believed to be superior to them all; so also the Life of all, our Lord and Savior, even Christ, did not devise a death for His own body, so as not to appear to be fearing some other death; but he accepted on the Cross, and endured, a death inflicted by others, and above all by His enemies, which they thought dreadful and ignominious and not to be faced; so that this also being destroyed, bot He Himself might be believed to be the Life, and the power of death be brought utterly to nought.

4. So something surprising has happened; for the death, which they thought to inflict as a disgrace, was actually a monument of victory against death itself. Whence neither did He suffer the death of John, his head being severed, nor, as Esaias, was He sawn in sunder; in order that even in death He might still keep His body undivided and in perfect soundness, and no pretext be afforded to those that would divide the Church.

Friday, January 06, 2012

Sonnet: The Epiphany of our Lord

The stars had always been a traveler’s friend,

Unerring maps in nighttime firmament,

But theirs was different. They learned to depend

On novel light: it led wheree’er they went,

Obeying laws unknown to sage or science.

And thus this star transfixed and guided them

To Herod’s, where he gave his feigned compliance

And sent them on to search in Bethlehem.

Rejoicing when the star came to a rest—

The end of their long journey now in view—

They found the child, and opening their chest

They offered gifts and paid him homage due.

O, Morning Star, this world is dark as night.

Pray draw all people to your wondrous light.

Unerring maps in nighttime firmament,

But theirs was different. They learned to depend

On novel light: it led wheree’er they went,

Obeying laws unknown to sage or science.

And thus this star transfixed and guided them

To Herod’s, where he gave his feigned compliance

And sent them on to search in Bethlehem.

Rejoicing when the star came to a rest—

The end of their long journey now in view—

They found the child, and opening their chest

They offered gifts and paid him homage due.

O, Morning Star, this world is dark as night.

Pray draw all people to your wondrous light.

Sunday, January 01, 2012

New Year's Day

The name of the film is "The Man Who Planted Trees," a Canadian short animated film directed by Frederic Back that is based on the French short story "The Story of Elzeard Bouffier, The Most Extraordinary Character I Ever Met" by Jean Giono. The film, with its simple yet evocative illustrations, claimed the Academy Award for best animated short film in 1987 and competed for the Canne Palm d'Or that same year. The English version of the film (there is a French one, too), is narrated by Christopher Plummer. There is very little dialogue in the movie. The action and intensity of the plot is conveyed solely by the voice of the inimitable Mr. Plummer, in his subtly dignified British accent, who simply reads what I assume to be the text of Giono's original story.

It is only 30 minutes long, but it seems much longer...and in a good way. It is not boring or pedantic. If a true epic ever were crammed into a half-hour, this is it. The plot sweeps through several decades, encompassing both World Wars. Without giving away too much of what happens, the story relates the utter transformation of an entire landscape and its citizens through the efforts of one, lone shepherd. It is one of those movies where you think, after watching, that it was a true story...or that it was at least based on a true story. For the first several years after viewing it for the first time, I refused to believe that it was pure fiction. Only here lately have I been able to make peace with that fact and realize that the beauty of the story lies not in any historical factuality. What the film illustrates may happen anywhere, at any time, in any number of ways.

And that is why I find it to be such a fitting movie for each new year. Its themes of new life amidst decay, new beginnings in the most inauspicious of surroundings, and large-scale metamorphosis through the painstaking repetition of small tasks are uplifting, to say the least. There are many books and stories and films that concentrate on these themes, but "The Man Who Planted Trees" seems to do it better (and more succinctly) than any other I have seen or heard of. The dedication and single-mindedness the shepherd Elzeard Bouffier applies to his task of tree-planting--an undertaking that only promises the most delayed gratification--is encouraging and inspiring for anyone who has ever been committed to some sort of long-term, ongoing activity.

More specifically, I find the story to be a wonderful allegory for ministry in the church. Conceived and written in a milieu much more agrarian than ours nowadays, the Scriptures often talk about planting and sowing, reaping and harvesting...albeit less about tree groves and more about wheatfields and vineyards. But the symbolism of the movie is easily to translate to the Bible. And, furthermore, "pastor" is Latin for "shepherd," Elzeard Bouffier's main vocation. So much of ministry in the life of the church is monotonous, and we have to wait a long, long time to see the fruits of our labors. We preach and teach, serve and visit, console and instruct, oftentimes never really telling if anything we do takes root. And this goes for the lay volunteers of the ministry of word and deed, not just the ordained ministers of word and sacrament. I suppose this allegory works for just about any job where you hope to "make a difference" in people's lives. But I find it really resonates for church work. Tending the gospel often feels like planting trees: it takes patience, sacrifice and vision for the long-term. The film's ending is so sweet and fulfilling that it gives me hope that our own tasks in Christian ministry may be so rewarded some day.

Lately, as I've watched the film, I have started to view things in a new way; namely, that Elzeard Bouffier is a Christ-figure. Some people disagree with me here...or at least they don't "see" it. But in some ways, I really like this interpretation of the story better. In this view, Elzeard is not so much a parallel for those of us working in the gospel fields, slogging steadily away at sowing the seeds of goodwill and peace with the hope of an eventual world (or congregation, at least!) transformation. Rather, we are desolate and war-torn hills where no water flows and no healthy life is found. We are the barren, dry landscape that everyone else would scratch off as hopeless. But then along comes one Planter who sacrifices every bit of time and energy he has to make us alive again. The presence (and absence) of water throughout the movie is a strong baptismal metaphor. Elzeard, the shepherd, is an example for us, yes, in how to work and accomplish something truly beautiful; but Elzeard is also, to my mind, a vision of the Good Shepherd. The world does not understand him and often mocks what he does. But he keeps at it, nevertheless, for the hope that these valleys can be verdant again.

No matter how it's viewed, the films offers an excellent reflection on the passage of time and the possibility of remarkable change. It is a great way to begin a year.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)